Rupert Loydell takes issue with ideas about evangelism now and back in the time of the 1970s and 80s Jesus Movement.

‘Evangelism was something I wouldn’t do to my dog, let alone my best friend.’ Rebecca Manley Pippart, Out of the Saltshaker & Into the World (1979)

I built myself a house of glass;

I took many years to make it:

And I was proud. But now, alas!

Would God someone would break it.

Edward Thomas, ‘I Built Myself a House of Glass’

‘Hearing about Christianity and understanding the choice are two different things. Not everyone understands Christianity is about grace and relationship. They think it’s about performance.’ Nathan Ketsdever, quora.com

Two things got me thinking recently. They were very different things, but I hope to explain the connection. The first was my own genuine confusion regarding Andrew Whitman’s new book, When Jesus Met Hippies: The Story and Legacy of the Jesus People Movement in the UK; the other a moment in London’s Oxford Street. Expecting a history of UK Jesus Music I was bewildered to be reading a book full of church-centred language, not to mention one that talked in terms of conversions, witness, outreach and the possibility of revival.

There is, of course, lots of intriguing documentation in Whitman’s book, as he explores the importation of attitude, dress sense and music from the USA, visits from Larry Norman, The Sheep and Arthur Blessitt, and the formation of organisations such as The Jesus Liberation Front, Deo Gloria Trust, Musical Gospel Outreach and the Greenbelt Festival. To me, however, it seemed like an attempt to reframe the past as something it wasn’t at the time.

Whitman uses a weird system of his own invention to hold figures, events and organisations from the past accountable, to tick off how their legacies and spirituality stood up then and now. And despite the author’s acknowledgement of the very wonderful John Peck’s theology of culture that underpinned Greenbelt Festival and College House (Cambridge), the book feels like it contains a subtext of disapproval, with many things seen as far too liberal and open to the world. One of the important things I learnt at Greenbelt was to be part of the world, to get stuck in and – as a writer and artist – be creative. And to be creative for the sake of creativity, not for any message or content, not as an excuse to preach or evangelise, not as a way to convince people to ‘be saved’.

Looking back at my own involvement with events in Whitman’s book (and I should say I corresponded a little with the author during the writing process, and am quoted on one page), I am mostly aghast at the way the censorious and right wing arm of traditional society and church were able to co-opt and misdirect young Christians into campaigning against ‘immoral’ television and films, against homosexuality, against allowing society to be the secular society it had become.

As a naive 10 year-old at the Festival of Light and then The Festival of Jesus, handing out special copies of Buzz magazine, putting stickers on lamp posts and accosting strangers so I could ‘witness’ to them, I was pretty much unaware of what was going on beyond the mass chorus singing, concert appearances by Parchment and Larry Norman, and the flotilla of banner-bedecked boats down the Thames. It was all a million miles away from the supportive, open-armed and engaging long weekends I later discovered at Greenbelt, having shaken off my happy-clappy Baptist youth club days.

But what, I hear you say, was the second event, in Oxford Street? It was a woman screaming at passers-by about Jesus, and that hell was waiting for everyone who didn’t know him. She was adamant that she was going to be there, standing on her chair, day in, day out, until everyone gave in. I hadn’t come under vocal fire from such abusive, bigoted and declamatory hellfire preaching for many decades. I’ve always wondered what people think they achieve by this kind of action, or how many people they can bully into signing up. Not many, I should think, on the evidence of the scurrying tourists and shoppers I saw.

I’m not accusing Whitman of encouraging this kind of thing, at all, although it does seem to be at an extreme end of what he is writing about. A few weeks after reading my review copy of his book, I ventured an email to him explaining my dilemma with regard to his narrative: that I just couldn’t see where I could review it. It wasn’t hippy enough or focused on music enough for International Times or academic enough for Punk & Post-Punk journal. Mostly, however, I just felt alienated from the story I was being told, a story I’d thought was going to be partly my story too.

I wanted a read that offered me nostalgia, some stories from back in the day, with obscure bands I’d never heard of, and explore the creative networks that burst out from churches into the real world, because that to me was what seemed important at the time – not a raid on society to take prisoners and return with them to the churches, counting converts’ scalps. I wanted to understand how the Jesus People changed the world, embraced the counterculture and joined in the revolution, not meet examples of individuals who had their lives spiritually changed or read about those who worked with people without any real social engagement, seeking only ‘conversions’ and ‘witness’.

Ship of Fools magazine may not have been central to the debates about culture, spirituality and the arts which were happening in the 70s and on into the 80s, but it was definitely part of it, asking questions, listening to answers, trying to understand what was going on, even as it sometimes satirised them. Other magazines, groups, churches and organisations opened themselves to discussions about creativity, gender, sexuality, and other faiths.

If you were sure of what you believed, then why would a witch or Hindu, who believed something else, be a threat? Why were many parts of church organisations so illiberal except when it came to finance, investment and property holdings, where wealth accumulation was somehow OK? And why did no one talk about AIDS?

Soon, of course, there were other festivals, full of neat and tidy, inoffensive bands playing to Sunday school and church youth group members being kept away from dangerous views and difficult questions, and casually dressed preachers whose sermons could have been written 200 years ago. And there were mega-churches imported from America that made it hip to be seen as both wealthy and religious. The counterculture was quickly assimilated, abandoned or went underground (large parts of it, it seems in Cornwall, where I now live).

Despite numerous theological, academic and social science books about secularism, post-evangelism, postmodernity, and how Western society has changed on the back of the social web and other technologies, it seems we have not changed our thinking. Most Christians prefer to keep themselves uninformed and disengaged, trying to keep our cold Victorian and medieval buildings open for the few who use them, rather than think about what church is or might be.

Theories are just that – theories – but they are also useful ways of understanding things. The adoption of the rhizome model, by French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, as an example of how society is now based upon networks rather than hierarchies, is one such useful idea. (Think about how potatoes spread, and how all the individual potatoes are equal parts of the plant.) Guy Debord’s book, The Society of the Spectacle (1967), explained how what appears to be happening – the spectacle of modern life – is not what is necessarily happening, but is a facade created by ourselves and others, as spectacle. We might consider that in relation to the Festival of Light, and how people construct images for their online selves in WhatsApp.

Don Cupitt’s writing in Radicals and the Future of the Church (1989), despite his disbelief in any metaphysical God, remains a visionary statement of what the church might become: useful, relevant and rooted in ritual and community.

I confess that in my own paranoid and suspicious way, I conflate right wing politics, large parts of the organised church, the prosperity gospel of money-grabbing churches, and the ridiculous assumption that the Bible is somehow literally ‘the word of God’ – despite the contradictions, versions, violence, sexism and complexities of the texts we have chosen to include or exclude as scripture. I keep returning to the idea that God is creative, that Jesus spoke in parables, using metaphors, similes and puzzles, that all we are asked to be is ourselves, wherever and whoever we are.

We are not encouraged to round up and count converts, run persuasive outreach missions, or make everything Christian, let alone religious, and certainly not nice. We are told to work in our communities, help those who need help, discuss, debate and share, not criticise, censor and accuse. There is no hierarchy of wrongdoing, no good or bad scores to be awarded or taken away, least of all by us.

Something that changed for the better in the last couple of decades is that people will openly discuss spirituality and belief. I’d much rather keep doing that in our village pub with a pint of beer than shouting at people to go to hell.

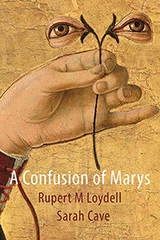

Rupert Loydell is Senior Lecturer in the School of Writing and Journalism at Falmouth University, a writer, editor and abstract artist. He has many books of poetry in print, including A Confusion of Marys, with Sarah Cave (Shearsman Books, 2020). Read a conversation between Rupert Loydell and Sarah Cave, Angels, aliens, and annunciations. Photo by David Henry

Photo by David Henry